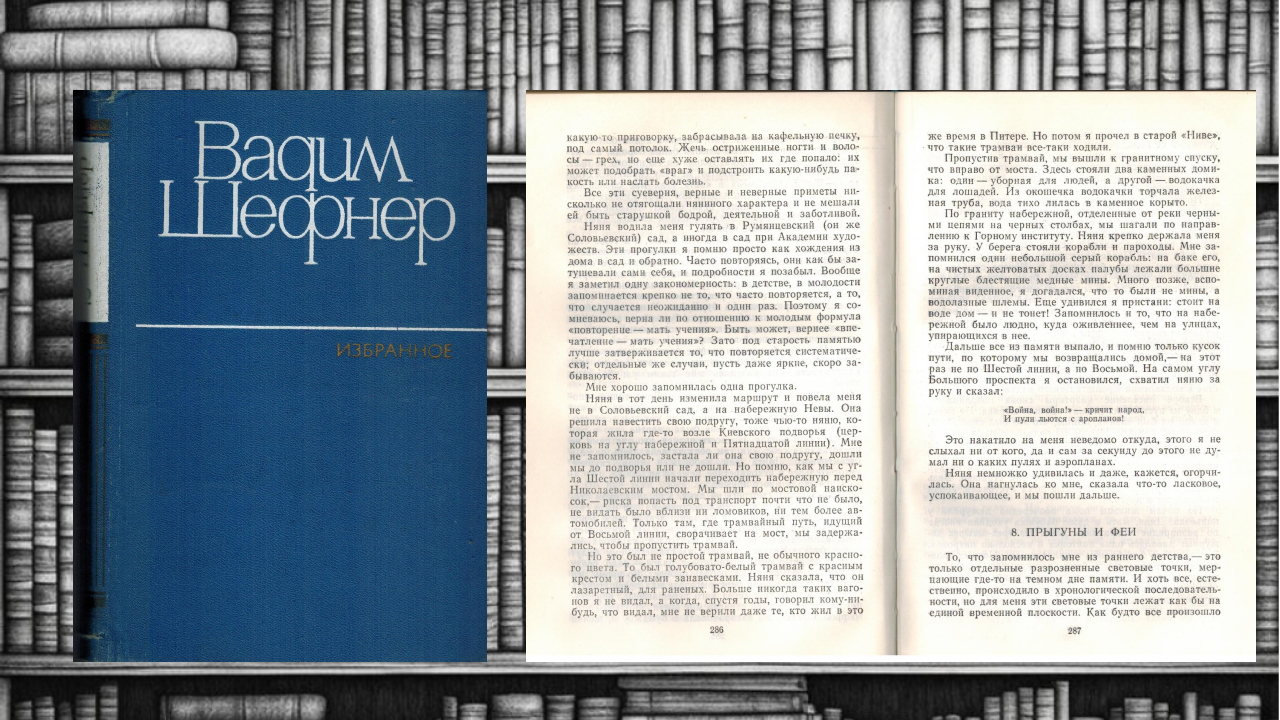

Dear friends, today I present to you the novel by Russian Soviet prose writer, poet, translator, fantasist, journalist, and frontline correspondent Vadim Shefner – “Sister of Sorrow”.

Excerpt from the novel:

“I said goodbye to Veranda, got on the tram, and headed to Vasilievsky Island. But upon getting off the tram, I didn’t go straight home. On days when something unpleasant happened, I liked to wander the streets – it made me feel better. The city was my old friend, and it always helped me in its own quiet way. It didn’t interfere with my sorrows – it silently took them upon itself. I was born in it, in one of its houses, but which street, in which house – only it knew, because I was abandoned as a child and couldn’t remember or know my parents.

The March twilight quietly layered over Vasilievsky, and it lit up its evening lights. Not long ago, the city was darkened, only the blue bulbs in the entrances were lit. But two weeks ago, the blackout was lifted. The city burst into light, like a train emerging from a long tunnel. I walked down the street and watched rectangles of windows light up on the dark walls. Their light was cozy and festive. It seemed that all the houses had long been filled to the brim with this warm, cozy light, but until now, it was visible only to those who lived in these houses. And now, in the snowy twilight, someone, with a giant silent stamp, cuts out rectangles in the dark walls – and the light rushes outward. In the distance, where it seemed there was nothing but twilight and gray sky over snowy roofs, a light tower appeared: several windows, one above the other, and – on top – a round window. Some kind of janitor-magician pressed the stairwell switch and in an instant erected this tower.

I walked onto the bustling Middle Avenue and headed towards the Harbor, but then turned onto the line of Melancholy Reflections. On days of misfortune and hardship, I liked to walk down this quiet street. Of course, officially it wasn’t called that, I gave it that name. The thing is, on Vasilievsky, almost all the lines-streets were nameless, they only had numbers. And I never liked numbers, digits, and codes. So, I gave some of the Vasilievsky lines my own names. I used these names alone; for all other people in the world, they had no meaning. I had the Beer Line – there was a cozy pub where Kostya, Grisha, Volodya, and I sometimes dropped by; there was the Dog Street – for some reason, dog owners always walked their dogs there; there was the Sausage Line – we bought sausages at the store there; there was the Funeral Line – funeral processions passed through Smolensk; there was the Interesting Line – once in the summer, I saw a man riding a bicycle on it, wearing a wooden toilet seat around his neck – there was no luggage rack on the bike, and this was the only way out for the cyclist; from the outside, it looked very interesting. I had to rename one line. Once I found a fight there and called it Happy, but soon it turned out that Kostya and I got into a fight on this street, and the odds were not in our favor; we got a beating. I had to rename this line from Happy to Fightful. And now I walked along the line of Melancholy Reflections and reflected on today’s troubles. From the quiet line of Melancholy Reflections, I turned onto the Avenue of Wonderful Inaccessible Girls – this was the Big Avenue VO. But for me, it was the Avenue of Wonderful Inaccessible Girls. In the evenings, it was very lively here, something like a promenade was happening. Here you could see all sorts of girls, and in the twilight, they all seemed so beautiful and charming. I knew that some guys even met girls here, but I could only envy the courage of these guys. I myself was bold and uninhibited only with Veranda and a few other girls – but they were just ordinary girls. And along the Avenue of Wonderful Inaccessible Girls, there were extraordinary, unapproachable girls.”

The collection also includes other works by the author: “A Name for a Bird, or Tea Party on the Yellow Veranda,” written in the best traditions of autobiographical prose, and the fantastic humorous stories “Modest Genius” and “The Round Mystery.”